P2 明星员工与企业 (We have Star performers!)原文:

A

The difference between companies is people. With capital and technology in plentiful supply, the critical resource for companies in the knowledge era will be human talent. Companies full of of achievers will, by definition, outperform organisations of plodders. Ergo, compete ferociously for the best people. Poach and pamper starts; ruthlessly weed out second-raters. This in essence has been the recruitment strategy of the ambitious company of the past decade. The “talent mindset” was given definitive form in two reports by the consultancy McKinsey famously entitled The War for Talent. Although the intensity of the warfare subsequently subsided along with the air in the internet bubble, it has been warming up again as the economy tightens: labour shortages, for example, are the reason the government has laid out the welcome mat for immigrants from the new Europe.

B

Yet while the diagnosis--people are important--is evident to the point of platitude, the apparently logical prescription--hire the best--like so much in management is not only not obvious: it is in fact profoundly wrong. The first suspicions dawned with the crash to earth of the dotcom meteors, which showed that dump is dumb whatever the IQ of those who perpetrate it. The point was illuminated in brilliant relief by Enron, whose leaders, as a New Yorker article called “The Talent Myth” entertainingly related, were so convinced of their own cleverness that they never twigged that collective intelligence is not the sum of a lot of individual intelligences. In fact in a profound sense the two are opposites. Enron believed in stars, noted author Malcolm Gladwell, because they didn`t believe in systems. But companies don`t just create: “they execute and compete and co-ordinate the efforts of many people, and the organisations that are most successful at that task are the ones where the system is the star”. The truth is that you can`t win the talent wars by hiring stars--only lose it. New light on why this should be so is thrown by an analysis of star behaviour in this month`s Harvard Business Review. In a study of the careers of 1, 000 star-stock analysts in the 1990s, the researchers found that when a company recruited a star performer, three things happened.

C

First, stardom doesn`t easily transfer from one organisation to another. In many cases, performance dropped sharply when high performers switched employers and in some instances never recovered. More of success than commonly supposed is due to the working environment--systems, processes, leadership, accumulated embedded learning that are absent in and can`t be transported to the new firm. Moreover, precisely because of their past stellar performance, stars were unwilling to learn new tricks and antagonised those (on whom they now unwittingly depended) who could teach them. So they moved, upping their salary as they did-36 per cent moved on within three years, fast even for Wall Street. Second, group performance suffered as result of tensions and resentment by rivals within the team. One respondent likened hiring a star to an organ transplant. The new organ can damage others by hogging the blood supply, other organs can start aching or threaten to stop working or the body can reject the transplant altogether, he said. “You should think about it very carefully before you do a transplant to a healthy body. ” Third, investors punished the offender by selling its stock. This ironic, since the motive for important stars was often a suffering share price in the first place. Shareholders evidently believe that the company is overpaying, the hire is cashing in on a glorious past rather than preparing for a glowing present, and a spending spree is in the offing.

D

The result of mass star hirings as well as individual ones seem to conform such doubts. Look at County NatWest and Barclays de Zoete Wedd, both of which hired teams of stars with loud fanfare to do great things in investment banking in the 1990s. Both failed dismally. Everyone accepts the cliche that people make the organisation--but much more does the organisation make the people. When researchers studied the performance of fund managers in the 1990s, they discovered that just 30 per cent of variation in fund performance was due to the individual, compared to 70 per cent to the company-specific setting.

E

That will be no surprise to those familiar wit systems thinking. W Edwards Deming used to say that there was no point in beating up on people when 90 per cent of performance variation was down to the system within which they worked. Consistent improvement, he said, is a matter not of raising the level of individual intelligence, but of the learning of the organisation as a whole. The star system is glamorous--for the new. But it rarely benefits the company that thinks it is working it. And the knock--on consequences indirectly affect everyone else too. As one internet response to Gladwell`s New Yorker article put it: after Enron, “the rest of corporate America is stuck with overpaid, arrogant, underachieving, and relatively useless talent. ”

F

Football is another illustration of the stars vs systems strategic choice. As with investment banks and stockbrokers, is seems obvious that success should ultimately by down to money. Great players are scarce and expensive. So the club that can afford more of them than anyone else will win. But the performance of Arsenal and Manchester United on one hand and Chelsea and Real Madrid on the other proves that it`s not as easy as that. While Chelsea and Real Madrid have the funds to be compulsive star collectors--as with Juan Sebastian Veron--they are less successful than Arsenal and United which, like Liverpool before them, have put much more emphasis on developing a setting within which stars-in-the-making can flourish. Significantly, Thierry Henry, Patrick Veira and Robert Pires are much bigger starts than when Arsenal bought them, their value (in all sense) enhanced by the Arsenal system. At Chelsea, by contrast, the only context is the stars themselves--managers with different outlooks com and go every couple of seasons. There is no settled system for the stars to blend into. The Chelsea context has not only no added value, it has subtracted it. The side is less than the sum of its exorbitantly expensive parts. Even Real Madrid`s galacticos, the most extravagantly gifted on the planet, are being outperformed by less talented but better-integrated Spanish sides. In football, too, stars are trumped by systems.

G

So if not by hiring stars, how do you compete in the war for talent?You grow you own. This worked for investment analysts, where some companies were not only better at creating stars but also at retaining them. Because they had a much more sophisticated view of the interdependent relationship between star and system, they kept them longer without resorting to the exorbitant salaries that were so destructive to rivals.

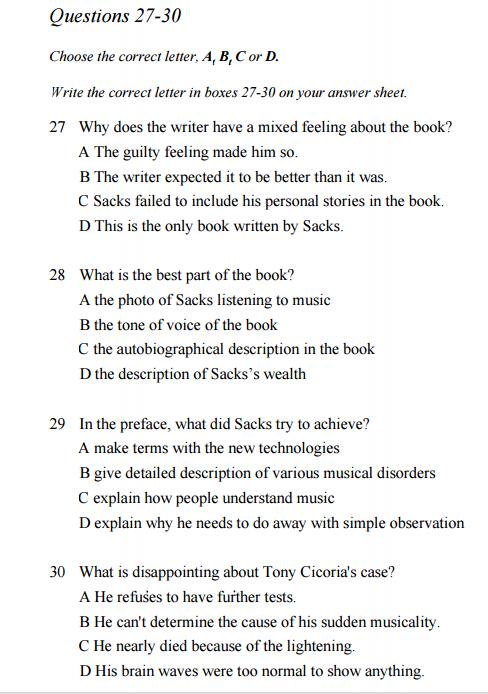

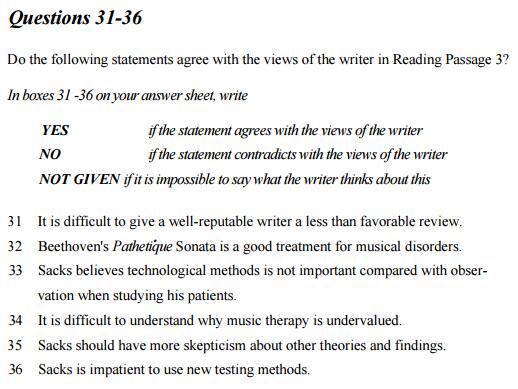

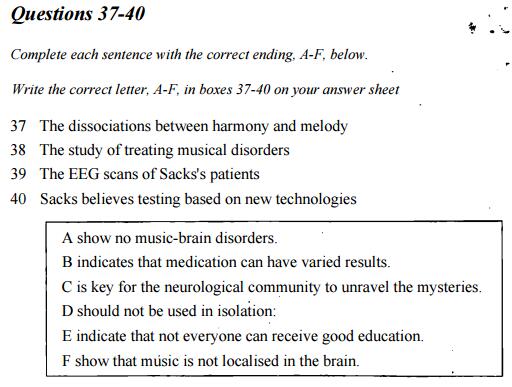

Questions 14-17

The Reading Passage has seven paragraphs A-G.

Which paragraph contains the following information.

Write the correct letter A-G, in boxes 14-17 on your answer sheet.

14 One example from non-commerce/business settings that better system wins bigger stars . .............

15 One failed company that believes stars rather than system ..............

16 One suggestion that author made to acquire employees then to win the competition nowadays ..............

17 One metaphor to human medical anatomy that illustrates the problems of hiring stars. ..............

Questions 18-21

Do the following statement agree with the information given in Reading Passage?

In boxes 18-21 on your answer sheet, write

TRUE if the statement agree with the information

FALSE if the statement contradicts the information

NOT GIVEN if the information is not given in the passage

18 McKinsey who wrote The War for Talent had not expected the huge influence made by this book. ..............

19 Economic condition becomes one of the factors which decide whether or not a country would prefer to hire foreign employees. ..............

20 The collapse of Enron is caused totally by a unfortunate incident instead of company`s management mistake. ..............

21 Football clubs that focus making stars in the setting are better than simply collecting stars. ..............

Questions 22-26

Summary

Complete the following summary of the paragraphs of Reading Passage, using NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the Reading Passage for each answer. Write your answer in boxes 22-26 on your answer sheet.

An investigation carried out on 1000 23.............. participants of a survey by Harvard Business Review found a company hire a 22.............. has negative effects. For instance, they behave considerably worse in a new team than in the 24.............. that they used to be. They move faster than wall street and increase their 25.............. Secondly, they faced rejections or refuse from those 26.............. within the team. Lastly, the one who made mistakes had been punished by selling his/her stock share.

参考答案

1. F

2. B

3. G

4. C

5. Not Given

6. Yes

7. No

8. Yes

9. analysts\ star-stock annlysts

10. performance start \ star performer

11. working environment\ settings

12. salary

13. rivals

P3 音乐心理书评

大意:是一本叫做Musicophilia的书的book review。讲到了与音乐相关的大脑/神经/心理的奇异现象,涉及到音乐对于病例的影响,比如使帕金森患者痊愈等。 Norman M. Weinberger reviews the latest work of Oliver Sacks on music.

A

Music and the brain are both endlessly fascinating subjects, and as a neuroscientist specialising in auditory learning and memory, I find them especially intriguing. So I had high expectations of Musicophilia, the latest offering from neurologist and prolific author Oliver Sacks. And I confess to feeling a little guilty reporting that my reactions to the book are mixed.

B

Sacks himself is the best part of Musicophilia. He richly documents his own life in the book and reveals highly personal experiences. The photograph of him on the cover of the book which shows him wearing headphones, eyes closed, clearly enchanted as he listens to Alfred 1 Brendel perform Beethoven's Pathitique Sonata--makes a positive impression that is borne out by the contents of the book. Sacks's voice throughout is steady and erudite but never pontifical. He is neither self-conscious nor self-promoting.

C

The preface gives a good idea of what the book will deliver. In it Sacks explains that he wants to convey the insights gleaned from the ^enormous and rapidly growing body of work on the . neural underpinnings of musical perception and imagery, and the complex and often bizarre disorders to which these are prone." He also stresses the importance of Mthe simple art of observation" and Mthe richness of the human context.He wants to combine observation and I description with the latest in technology,” he says, and to imaginatively enter into the expe-rience of his patients and subjects. The reader can see that Sacks, who has been practicing neurology for 40 years, is torn between the old-fashionedw path of observation and the new-fangled, high-tech approach: He knows that he needs to take heed of the latter, but his heart lies with the former.

D

The book consists mainly of detailed descriptions of cases, most of them involving patients whom Sacks has seen in his practice. Brief discussions of contemporary neuroscientific reports are sprinkled liberally throughout the text. Part I, MHaunted by Music," begins with the strange case of Tony Cicoria, a nonmusical, middle-aged surgeon who was consumed by a love of music after being hit by lightning. He suddenly began to crave listening to piano music, which _ he had never cared for in the past. He started to play the piano and then to compose music,1 which arose spontaneously in his mind in a u torrentw of notes. How could this happen? Was I the cause psychological? (He had had a near-death experience when the lightning struck him.) Or was it the direct result of a change in the auditory regions of his cerebral cortex? Electro-encephalography (EEG) showed his brain waves to be normal in the mid-1990s, just after his trauma and subsequent Mconversionw to music. There are now more sensitive tests, but Cicoria has declined to undergo them; he does not want to delve into the causes of his musicality. What a shame!

E

Part II, “A Range of Musicality,” covers a wider variety of topics,but unfortunately,some of the chapters offer little or nothing that is new. For example, chapter 13, which is five pages long, merely notes that the blind often have better hearing than the sighted. The most interesting chapters are those that present the strangest cases. Chapter 8 is about “amusia,”an inability to hear sounds as music, and “dysharmonia,”a highly specific impairment of the ability to hear harmony, with the ability to understand melody left intact. Such specific dissociationsw are found throughout the cases Sacks recounts.

F

To Sacks's credit, part III, "Memory, Movement and Music," brings us into the underappreciated realm of music therapy. Chapter 16 explains how "melodic intonation therapy" is being used to help expressive aphasic patients (those unable to express their thoughts verbaDy following a stroke or other cerebral incident) once again become capable of fluent speech. In chapter 20, Sacks demonstrates the near-miraculous power of music to animate Parkinson’s patients and other people with severe movement disorders, even those who are frozen into odd postures. Scientists cannot yet explain how music achieves this effect.

G

To readers who are unfamiliar with neuroscience and music behavior, Musicophilia may be something of a revelation. But the book will not satisfy those seeking the causes and implications of the phenomena Sacks describes. For one thing, Sacks appears to be more at ease dis* cussing patients than discussing experiments. And he tends to be rather uncritical in accepting scientific findings and theories.

H

It's true that the causes of music-brain oddities remain poorly understood. However, Sacks could have done more to draw out some of the implications of the careful observations that he and other neurologists have made and of the treatments that have been successful. For example, he might have noted that the many specific dissociations among components of music comprehension, such as loss of the ability to perceive harmony but not melody, indicate that there is no music center in the brain. Because many people who read the book are likely to believe in the brain localisation of all mental functions, this was a missed educational opportunity.

I

Another conclusion one could draw is that there seem to be no Mcuresff for neurological problems involving music. A drug can alleviate a symptom in one patient and aggravate it in another, or can have both positive and negative effects in the same patient. Treatments mentioned seem to be almost exclusively antiepileptic medications, which "damp down" the excitability of the brain in general; their effectiveness varies widely.

J

Finally, in many of the cases described here the patient with music-brain symptoms is reported to have "normal" EEG results. Although Sacks recognises the existence of new technologies, among them far more sensitive ways to analyze brain waves than the standard neurological EEG test, he does not call for their use. In fact, although he exhibits the greatest compassion for patients, he conveys no sense of urgency about the pursuit of new avenues in the diagnosis and treatment of music-brain disorders. This absence echoes the book's preface, in which Sacks expresses fear that wthe simple art of observation may be lost" if we rely too much on new technologies. He does call for both approaches, though, and we can only hope that the neurological community will respond.

答案:

27.B 28.C 29.A 30.A 31.YES 32. NOT GIVEN 33.NO

34.NOT GIVEN 35.YES 36.NO 37.F 38.B 39.A 40.D